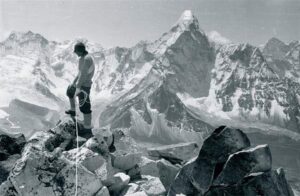

Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were the first two human beings to reach the top of Mount Everest, and return. I know very little about this attempt, but I do very strongly suspect a few things.

Firstly, that climbing this mountain was not something that was thought on the spur of the moment as a handy way to kill an afternoon.

“What are you doing today Tenzig?”

“Nothing, you?”

“Same. Say, why don’t we hike over and climb that hill over there?”

This grand attempt had to be planned, and grandly so.

The next thing that I know, is that Sir Hillary and Mr. Norgay did not stop five yards from the summit, and then say “Eh, good enough.” Absent the top, the mountain is not climbed.

Five yards short may have well been five miles, or five hundred miles, or as good as never leaving the house, sitting on your couch and watching the Reds’ game. Progress is good, but if it does not make it to completion- to the 100th percentile- the effort is a failure. It is either finished, or it is not.

Humans all make plans, we are planning beings, and need the plan both small and grandiose, as it is in our intellectual biology. Plans will range from the way to kill an afternoon, to an assault on Everest: but the big plan, the really important one, is what one does with oneself.

The dangerous and difficult plan is to act as a change agent, when change of oneself or an organization is necessary. New thinking is necessary to better an old circumstance, but it is not always welcome.

While I cannot give much good advice as to where the top of your mountain will be, my intention is to speak about the framework of this planning- meaning strategic planning- and advice on navigating clear of obstacles.

Vision.

This represents a more holistic thought process that determination of the destination, which is by surprise is the second step. It is not enough to set one’s sights on the top of Everest, one must visualize what the world will look like, and how it can be shaped to his will. On the top of the mountain, vision and destination will be the same, but a broader view allows for more creative thinking and consideration of options.

If the vision is to see the Pacific, this can be done in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Washington State, etc. The vision coalesces in the mind, and determines what the world should look like, and in such that vision becomes primary and the destination subordinate.

This is where the planner will have the most difficulty. The enemy is one of previous experience, as I do know what the Pacific looks like from all three vantages, and a few more. This historical perspective could cloud the vision, and it requires some insight to become original if the plan has been done before. Expectation can be an enemy, certainly a limitation, if not truly visionary.

Vision determines which end state has the most value, the most potential, and in real terms, the most feasible. If I had the desire to climb Everest, which, plainly, I do not- I would run into issues with feasibility. Feasibility, or really lack thereof, is where vision becomes nothing more than a dream, or a nice thought, and beyond execution.

Destination.

Once we have determined vision, what the world should look like and its feasibility, destination becomes the next important consideration. Otherwise, how does know when the plan is complete? To climb Everest, one must get to the top.

The other reason that destination is subordinate to vision, is for the sake of phased operations, or initial and subsequent destinations, all that will require different work plans, or what we will call “Lines of Effort”.

Lines of Effort.

Broken down in a work plan, these are the broad actions that enable strategic origins. Simply stated, if work does not propel organizational travel towards destination and vision, then it must be excluded, ignored, or discarded. This requires discipline.

Lines of effort includes readiness, resources, enablers, branches, sequels, and other factors that ensure the effort is mobile from origin to vision realization. Physical stamina is a valid one if one is a mountain climber, reliable transportation and vehicle readiness is one wishes to see the Pacific. Other considerations that enable feasibility as separate priorities of work. Funds, certainly. It takes money to get to Nepal, and also to fill up the truck at Speedway if a road trip is at hand.

The larger the enterprise, the more work must be done; but it is clear that ejecting the unnecessary must hold here, so not too many. It is understood that the lines of effort will one day intersect when the visionary reality is at hand. Otherwise, one’s priority of work is the literal traveling portion of the journey.

Partnerships and Consensus.

If this is a team-oriented task beyond the individual, communication planning becomes a priority of work. Team attributes are leveraged towards completion, which requires team member consensus and support. Team members may or may not share the vision, so absolute consensus is not required, but teammates must see the value in supporting the journey, at the very least.

Communication and justification are a task that requires continual maintenance. The vision holder, the primary leader of the enterprise, must repeat himself often to get the proper amount of support. The more distant the destination, the more often the leader must repeat himself. Again, it must be supported, maintained, seen as valuable, but communication is the grease that keeps the machine running.

Obstacles, constraints, and limitations.

These are those issues that are discovered through navigating through the work plan. As unexpected, and detrimental, their position- in the middle and in the way- require address. Feasibility is in great amount is measured by flexibility, bypassing these obstacles and not becoming broken by them. If the plan absolutely relies on one particular piece to fall into place, it is normally obvious during the initial visionary process. The remainder, lessor evils, must be dealt with in order, as they appear.

Materials are obvious, people are not. The same team members that applauded the construction of the primary building blocks can become discouraged during the working portion. If their good faith contribution is essential, double/ triple down on communication, if they are unnecessary- bypass them, if they can be replaced, find another- even if those closing steps must be done by oneself. Your completion, if vested in one person/ team/ entity; who becomes an obstacle and is who is otherwise irreplaceable- represents the single most reason for failure.

The Last Five Yards.

These are the toughest, the last few steps before destination. This is where team members, especially those effected even on the periphery, will start to pull back, and try to pull you back on the course further back down the hill from destination.

Those that are not vested, do not see value, will be fearful of one that is nearing the summit. People are naturally fearful of change, even to the point that they will embrace what they despise or what has failed in the past. The final rejection of change becomes the complete attempt for the body of this community to repel what they see as infection of their changing world, despite if the outcome is healthier.

This is where one will hear the phrase, “we can’t because.” No single phrase has killed more visionary journeys than this phrase. Motives unclear, suspicions certain, a journeyman may have to carry the entire weight of those that say “we can’t because” the last five yards.

These individuals are fairly easy to recognize, so planning for this step is hard, but straightforward. The “you can’t because”, are the same people that have done no work, and will say after you’ve done the work, and are standing on the summit, “I would have done it this way.”

Bear down. Force it. The summit of Everest is right there. Turning back now is a waste of sweat. Climb it.

I’ll see you on the summit.